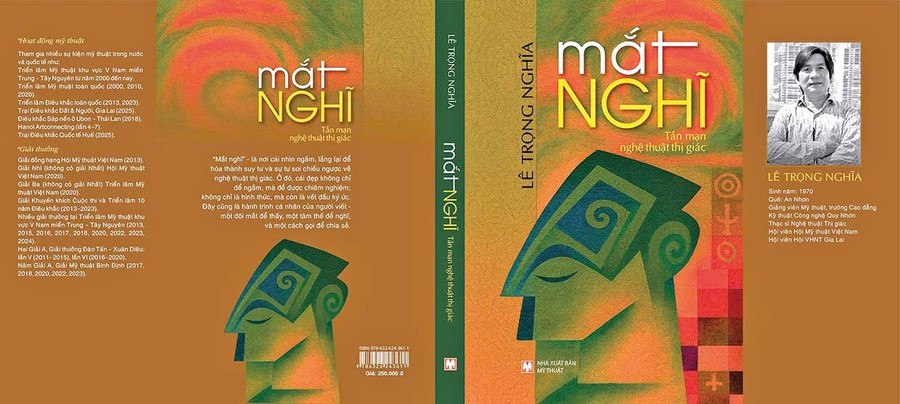

The book is a collection of notes, reflections, and contemplations by the author, charting a parallel journey between form and thought.

* Why did you choose the title “Mắt nghĩ” (“Thinking Eyes”)?

- I believe that eyes, beyond their visual function, are also for thinking and empathizing. When the eyes are allowed to think, they cease to be mere sensory organs and become an independent consciousness—a place where emotion, memory, and perception converge. To me, every pair of eyes has its own voice, its right to think, to feel, to err, and to love.

Thus, “Thinking Eyes” is not just a title, but an artistic attitude: daring to see with intuition, daring to think with emotion. When we allow our eyes to think, art becomes more accessible, people become more authentic, and beauty gains a soul.

* Could you introduce the structure of the book? Why did you choose the form of “artistic essays” instead of research or monograph?

- “Thinking Eyes” consists of 55 pieces, divided into five sections: Origin, Dialogue, Philosophy, Imperfection, and Rebirth—like five stages of a creative journey. I chose the essay form because it is closer to the essence of art—not a system of arguments, but a journey of emotions...

* What role does writing play in your creative process?

- Writing is another form of sculpture—sculpting with words. When I write, I am not recounting the creative process, but engaging in a dialogue with myself, with the silences my hands have yet to touch. In sculpture, I converse with material; in writing, I converse with the soul of form. Both seek the “soul of form,” the voice of beauty.

* Many pieces in the book show your interest in “memory” and “traces.” Could you elaborate?

- Memory is the intangible material of visual art. Art is born from the obsession to resist oblivion. From the Dabous giraffe carvings to the worn and broken Cham statues, all are voices of time. When I touch a crack on a statue, I hear the hands of those who came before. Between us, time does not divide, but is a long dialogue of souls who know how to shape. In both sculpture and writing, what I seek is not just form, but the traces of life left in the material.

* Prehistoric Venuses, the Dabous giraffe, Pompeii, or Sumerian cuneiforms appear frequently in your work. What do they reflect about your view of today’s art world?

- I turn to these figures not out of nostalgia, but to recognize the first breath of art—where humans first carved, molded, and wrote to speak of themselves. The Venus figurines are small yet fierce, Pompeii is tragic yet still vibrant in its ashes, and the Sumerian cuneiforms, though austere, evoke a lesson in simplicity—that a single incision can carry a soul.

All of these show me a red thread connecting civilizations. Beauty, no matter how much dust it endures, always finds a way to be reborn.

* You once said “imperfection” is also a form of beauty. What does “the unfinished” mean in your creative process?

- I believe in the beauty of the incomplete. A crack in wood, a rough weld in iron—sometimes these are precisely where a work begins to have a soul. In the wounds of material, I seem to hear the whispers of time.

I find deep resonance in the Japanese philosophy of Wabi-sabi: beauty does not lie in perfection, but in the warmth of time left on objects, in the traces of life and loss lingering on the silent surfaces of stone, wood, and people. It is in this imperfection that art finds its soul, and people find themselves.

* In your view, is doubt a necessary element in artistic creation?

- Without doubt, the artist would sleep soundly. It is doubt that compels me to keep asking: Is beauty real? Is art still necessary? Yet within these questions, I find faith—that art exists to awaken, not to comfort. I do not fear doubt; I only fear certainty…

* In the past, Bình Định (now Gia Lai province), with its wealth of sculpture, architecture, and Cham heritage, has influenced your visual thinking. In your opinion, in the context of contemporary art, how can we connect heritage such as ancient Gò Sành ceramics or Cham sculpture with new visual languages while preserving the traditional soul?

- I grew up among the solemn Cham towers, shards of pottery mixed in the fields. The Cham heritage taught me that beauty is not in perfection, but in the vitality hidden in what remains. When I weld a rusty iron bar onto stone or attach an ancient ceramic shard to wood, it is a conversation between past and present. To connect heritage with new visual languages, we do not need to “renew” the past, but simply listen to it, to tell a different story in spirit, not in form.

* Thank you for the conversation!